'Baba' Murmurations, Agility in Flight

Fears, technology, learning from birds, and three simple principles for staying safe and coordinating big things.

I’ve had few fears or anxieties in life. Examples at the top of the list include falling down stairs, new social interactions, and birds flying at me.

The latter persisted until a few years ago when I faced it head-on while walking to lunch in downtown DC. A bird flew into my face. It fell to the ground, looked up at me, then off it went—along with the fear.

I didn’t appreciate birds as much until we moved to Annapolis. It’s home to the largest population of Ospreys, which coincidentally was my college mascot. It’s also considered a designated bird city, with policies and an environment that supports hundreds of varieties.

Being a bird city means showing commitment to wildlife conservation, being stewards of the environment, and engaging the community to protect birds.

There are really neat tools for appreciating birds, tracking them, and identifying them, like Cornell Lab’s Merlin, or the Audubon Bird Guide. Apparently there’s never been a better time to become a birder.

Bird watching has become a pastime. Our daughters call for the ‘babas’ and look for them in our yard and trees. All times of the year, and hours of the day, they sing.

As with seasons and shifting climates, bird populations change. We might see tundra swans in the winter, herons in the summertime. Birds have also been brought over and introduced, such as the European starling in the 19th century.

Starlings are considered one of the most adaptable avians. They’ve grown to live in most environments and can mimic the calls of other birds, mechanical sounds, and even humans.

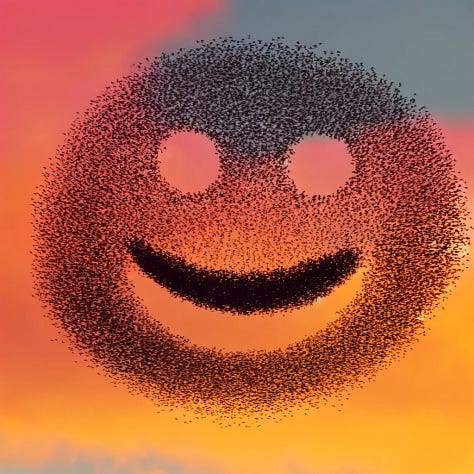

They come together to form majestic formations of called murmurations. Intricate and emergent moving patterns made by massive communities of starlings. Hundreds to hundreds of thousands of birds together, in one flock.

Thought to be a form of information-sharing, murmurations are both complex social interactions and security measures. They use the patterns to confuse predators and signal for safety. They form in the evenings, at sundown, before roosting. It only takes one or a few to start, but as others see their patterns, they join in.

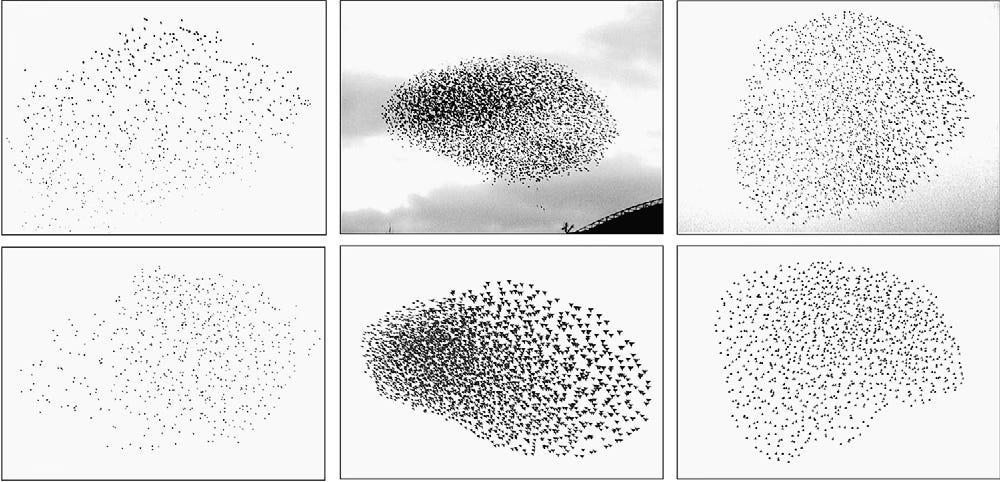

For ages, scientists were intrigued but didn’t know exactly how they did it. Some thought they were telepathic, but it wasn’t until digital recording, computer vision, and advanced modeling that we could understand them.

These brilliant birds look to the seven nearest birds around them and respond with incredible agility. Their brilliant coordination has been attributed to three key principles at flight:

Separation: Maintain minimum distance from others, avoid crowding to allow space for maneuvering

Alignment: Match velocity and direction of those closest to them

Cohesion: Move toward the average position between neighbors

Their process is fascinating and immediately transferable.

It’s been considered a model for building communities of practice. It could also be a model for scaling systems and responding to change.

It demonstrates the necessity for collaboration and responsiveness while observing and respecting boundaries. It emphasizes the importance of having guidance and structure and looking to those around you for support.

As I’ve pushed myself to be more and more social, and not fall on my face in future endeavors, I’ve started to look to others and am trying to embody this philosophy.

It only takes one or a few to start, but as others join, with these principles applied, they follow in to produce one of nature’s most captivating displays.